Vesemir: Our virtual machine deployment service

10 Jun 2021 #softwaredevelopment #deployments

This post is a continuation of the tweet here

The build and deployment pipeline for each org will be different in some way or the other, given each co will have it’s own requirements. This thread talks a bit about our virtual machine deployment pipeline (1/n)

— Tasdik Rahman (@tasdikrahman) June 10, 2021

This was also cross posted originally for the gojek tech blog https://www.gojek.io/blog/introducing-vesemir-gojeks-virtual-machine-deployment-service

The build and deployment pipeline for each org will be different in some way or the other, given each co will have it’s own requirements. Even in my last org, the way our team enabled other teams to ship code/config changes, was pretty different from the way we do it in my current org.

Background

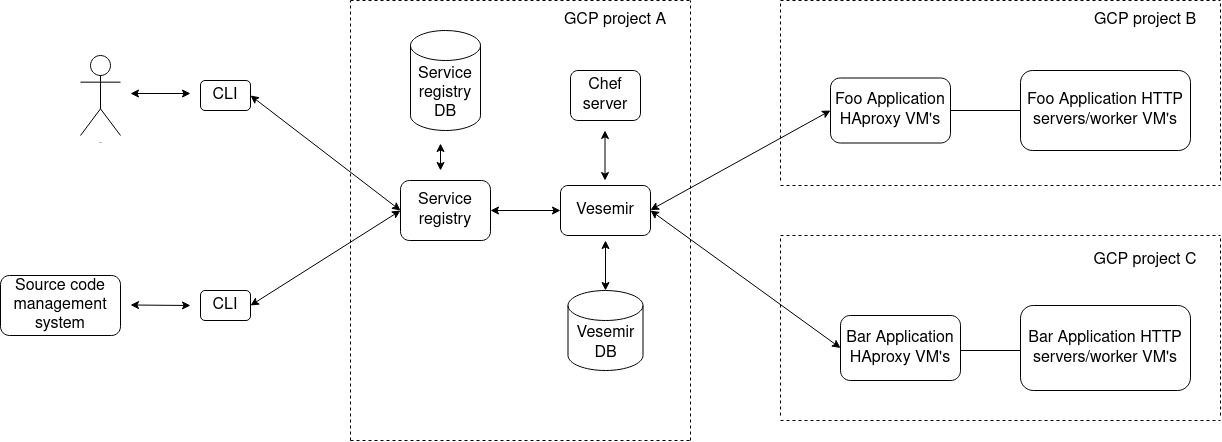

Our deployment platform comprises, of a central service registry, two separate services to deploy to virtual machines and kubernetes respectively, a cli to interact with the service registry, which is given out to the developers of the org using which they can do numerous things for their application in a self serve manner. One of those things, being the ability to deploy their applications via the CLI.

The idea is to abstract out the deployment process from the developers as much as possible, but also giving them the means to debug with the logs being shown to them, which are meaningful to them to figure out what went wrong if it doesn’t work as expected.

For this post, I will specifically talk about the virtual machine deployment service, called vesemir, which we have in place and how we went about revamping it’s infrastructure along with refactoring it to keep it healthy and maintainable for others to work on it’s codebase.

Given, GCP doesn’t have a service similar to AWS codedeploy, vesemir came out of the same requirement.

What does it really do?

Vesemir is a inhouse python service, which in a gist is a wrapper on top of chef API’s, where-in it receives a request for deploying a service in a particular cluster (a GCP project), filters out the VM’s where it has to deploy the changeset and then goes about deploying the changeset, either one at a time or at the level of concurrency insisted upon by the request.

It hels us deploy to integration and production environments, 300+ times every day.

How does it do it?

The initial request payload, bits which are of most relevance are

- application name

- environment

- team

- chef tags to be used for filtering the application VM’s

- haproxy metadata (degradation time specified, cookbook/recipe/tags to filter the haproxy boxes, haproxy backend)

- concurrency (number of VM’s to deploy at a time)

Once vesemir, receives this piece of information, it queries the chef server via pychef, with the information passed for the search tags, the query for which gets constructed and send to the central chef server. The hostnames and their IP’s then get parsed.

This takes care of the first bit of the problem where we know which VM’s are to be touched for deploying the changeset.

Along with this bit, the playbook.PlaybookExecutor gets initialised with the ansible playbook(more on this later) which we would be executing on the hosts found, the inventory file, and the variable manager named argument taking in extra variables which are going to be used by the templatised playbook.

We write the ansible inventory file in a temporary file, using NamedTemporaryFile which gets deleted after the whole request/response lifecyle for a deployment, which gets fed into the InventoryManager, where we pass the hostnamefile which we created above as sources

The ansible playbook which gets fed into playbook.PlaybookExecutor, is a static playbook with jinja templating, where we feed the options via the VariableManager into the extra_vars

The options named var, will take in details like, which user and other authz/authn details to be used by ansible to ssh into the hosts, along with options like forks where the concurrency is set for the number of boxes where we would want to run the playbook.

The next step is to execute the run method on the initialiazed object of playbook.PlaybookExecutor. The important bit here after the run is the collection of stats which we pick up, from the TaskQueueManager, which is what we then use to check for nodes where the playbook ran successfully or not, if the hosts were unreachable and so on.

This piece of information is then used to form a response to be given back to the client which has called vesemir.

As for the playbook and what does it do, in gist, it first, disables the server where it is first going to deploy, in the haproxy backend for the application servers. Introduces the changeset, restarts the service, enables this VM back in the HAproxy backend with weights if provided during the request, an option to sleep for a bit is also introduced which is again controlled by the request, before which the VM is inserted back with 100% weight.

The playbook is then looped over the hosts, returned by the chef query while searching, all while executing the playbook tasks on the hosts.

Pros of this deployment pattern

The obvious is since we control the deployment platform tooling, it allows for us to have a level of flexibility, not possible with vendors. Everything is more or less, an outcome of this flexibility which we get.

Shortcomings of this deployment pattern

Given the changelog is introduced in each VM in such a way, immutability is not possible, which is again to the AMI based approach, where AWS codedeploy would do something similar to inject the codebase into the target VMs.

More moving parts in the system, which depend on external dependencies. For eg: ansible being a very important part for vesemir to deploy the changeset, right from using piggybackin on the ssh interface provided, to the templatising of the steps of execution to be done.

Maintenance of a custom tool, which would have it’s own lifecycle, maintenance, bugs and feature requests.

Takeaways

There are numerous ways in which people end up deploying their codebases, but maintaining vesemir for sometime now for my current org, having seen both sides of having immutable deployments via container images, to deploying changeset via vesemir, it’s not very hard to see the selling point of immutability.

Thanks for reading this piece so far, more on how we ended up revamping vesemir in another post.

Links

- playbook.PlaybookExecutor class - https://github.com/ansible/ansible/blob/v2.5.1/lib/ansible/executor/playbook_executor.py

- VariableManager class - https://github.com/ansible/ansible/blob/v2.5.0/lib/ansible/vars/manager.py#L76

- TaskExecutor class - https://github.com/ansible/ansible/blob/v2.5.0/lib/ansible/executor/task_executor.py#L84

- TaskQueueManager class - https://github.com/ansible/ansible/blob/v2.5.0/lib/ansible/executor/task_queue_manager.py#L52

- https://github.com/coderanger/pychef

- Cover image credits